On the Surprising Effectiveness of Large Learning Rates under Standard Width Scaling

A primary goal of infinite-width theory has always been explaining neural networks as they are initialized and trained in practice (called ‘standard parameterization’, short SP). But there has always remained a fundamental gap: Existing theory for SP predicts a kernel regime with vanishing feature learning under small learning rates, and instability due to logit divergence under large learning rates. But even extensively large models continue to effectively learn features in practice, which results in favorable performance at scale. While previous works suggest strong finite-width or long-training time effects, we show that these explanations do not suffice. These insights were only enabled by sufficiently fine-grained tracking of network-internal signal propagation. In refined coordinate checks, we disentangle propagating updates from previous layers from effective updates in the current layer, which show surprisingly clean predicted update exponents, even over the course of training. We released a flexible, open-source package that enables fine-grained tracking of GPT internals such as refined coordinate checks (RCC) in a few lines of code. RCCs are an essential diagnostic tool for understanding whether your layerwise initialization and learning rate choices achieve model-scale-invariant forward and backward signal propagation. Check out our blog post for an accessible introduction.

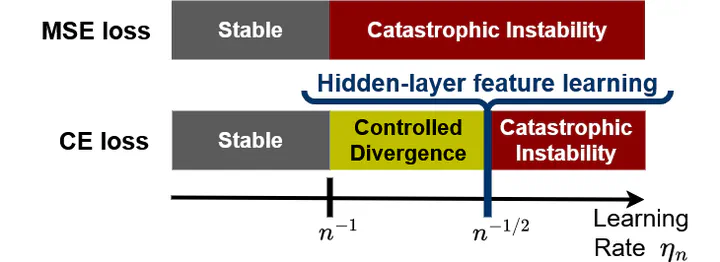

Instead this apparent gap between pessimistic infinite-width theory and well-performing practice can be fundamentally reconciled with the insight that logit divergence does not harm training stability when using torch.nn.CrossEntropyLoss (with a softmax before the cross-entropy loss). Consequently even extensively wide neural networks in SP trained with SGD (or Adam) under large learning rates effectively update all hidden layers. This has several important implications:

a) Our max-stable learning rate exponent predictions significantly constrain the search space for the optimal learning rate, even in practical settings like GPT pretraining. The optimal learning rate often even ‘approximately transfers’ across model scale under the scaling exponents predicted by our theory despite vanishing input layer feature learning and logit blowup in SP with large learning rates (for both SGD and Adam).

b) CE loss often outperforms MSE loss because large learning rates do not remain stable under MSE loss and consequently feature learning is lost at scale. Using muP at large model scale enables using other loss functions such as MSE loss.

c) We explain why SP-full-align from Everett et al. works so well: At large width, SP-full-align lies at the feature learning edge of the controlled divergence regime, where it remains stable despite logit divergence. In language settings (width « output dimension), standard initialization non-asymptotically preserves the variance of propagating updates even better than muP.

d) Overall, Tensor Program width-scaling exponent predictions for layerwise updates and maximal stable learning rates hold surprisingly accurately already at moderate scale and over the course of training. This allows predicting sources of training or numerical instability and finding principled solutions.

These insights uncover many exciting questions for future work. For example, training points are memorized increasingly sharply with model scale. On the one hand this might speed up learning, but on the other hand it hurts calibration. Overall, when does logit divergence help and when does it harm performance? Is this a fundamental reason for overconfident predictions in SP, and muP might be more calibrated? Similarly, should we boost input- and normalization layer learning rates at large scale, or is it a beneficial inductive bias to learn these weights increasingly slowly in large models? Not only CE loss, but also normalization layers and Adam stabilize training against miss-scaled signals and extend the controlled divergence regime, but numerical underflows can induce sudden unexpected instabilities at sufficient scale. Can we prevent such instabilities and design numerically scalable training and representation strategies?